By Michael Heim

Adelaide, South Australia

My parents were sort of proto-hippies. They were a generation too early to be real hippies, but when the movement happened in the mid 1960s, they recognised it immediately, and embraced it. My mother Jane was born in 1927 and by the 1950’s she was a species of hipster intellectual, into jazz and art, and gardening. My stepfather Bern had been brought up as a conservative working class admirer of Robert Menzies, until he started reading books by H.G. Wells and Upton Sinclair, and they turned him onto a Fabian socialist. They both became radicalised teachers in the 1960’s and that is how they met. In 1966 they bought a block of land in the Adelaide foothills and began to contemplate a return to the simple life of self-sufficiency and natural food, and in 1969 they bought a small farm at a place called Parawa south of Adelaide on the Fleurieu Peninsula and began to try to life a life of self sufficiency. They were wildly over-optimistic and under-prepared and very soon had to rejoin reality and take jobs as teachers again, but for a couple of years we lived without electricity and tried to grow vegetables and milk a cow and realise a type of rural fantasy. If you know the book Little house in the big woods by Laura Ingalls Wilder, that was my childhood reading.

Here are some photos of the house we built which give a sense of our romantic ideals.

One of the things my mother wanted to do was to spin and weave and make her own clothes, and it is one of those pieces of clothing that I have brought in to share.

The story of this jumper and cap is that we grew the lamb from a baby, I shore the sheep, my mother dyed the wool using dandelion flowers that we picked from around our house, and she spun the wool on a hand spinning wheel and knitted this jumper and hat. She also wove on a hand loom lovely belts and scarves. I wore this jumper all the time from the age of about twelve to the age of 17 when I got a bit too pompous and hip for it, but it was fantastically warm and weatherproof, for farm work, and I still wear the cap on cold winters days. I’m extremely proud of my parents for their determination and willingness to try and make something new and viable, even if in the end it was not sustainable. It was a wonderful way to spend a part of my childhood and I retain intense pleasurable memories of life spent out of doors, looking over the Southern Ocean from my bedroom window, and walking every morning and every evening through the mallee scrubland of our farm, falling into the creek often, suddenly finding myself right up close to kangaroos and echidnas and foxes and red bellied black snakes, and all manner of beautifully coloured birds; parrots, fairy wrens, green finches, black cockatoos, eagles. And where our creek flowed into the sea, a tiny beach of coarse red sand on a wild rocky oceanic coastline, we could watch schools of dolphins surfing for sheer pleasure and the sport of it.

Here is my mother Jane in full on peasant mode. It is probably as well that we didn’t actually have to rely on her for our clothing.

The sheep behind her shoulder is the one who provided the wool for the jumper.

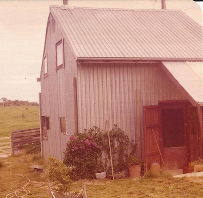

We started out living in this tin shack on a windy hilltop.

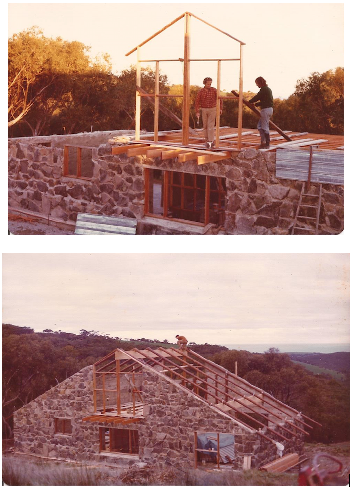

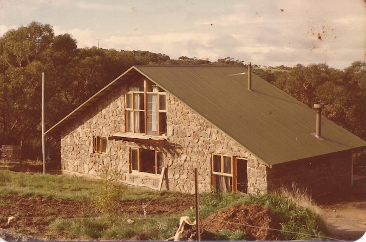

In 1977 Bern designed a house we would build, from scratch, using stone we collected from an outcrop in a valley nearby. Bern had been a builder when he was young, so he almost knew what he was doing. These photos show the stages of construction.

This was the view down the valley

On the inside clean white walls exposed beams and a wood heater.

And here they are, Jane and Bern, looking relaxed and neat and happy.

Thank you for reading what has become a little homage to a very humane idea and a couple of very humane people who tried to make it work. I have drawn a quite idyllic vision of life at the farm. The whole project was a part of a stream of idealistic philosophy that held some sway in the 1960s and 70s. If I can think about it as a historian for a moment, the thing I find interesting is the level of “golden ages of the past” thinking that lies underneath it. Those ideas reach back far into the past of course, but specifically to the nineteenth century and figures like the utopian socialist Robert Owen, or the Arts and Crafts Movement of William Morris, or even a religious mystic like the poet William Blake. My parents wanted to reject modern technology as too complex and somehow inhuman, and they tried to construct something different.

My personal feeling, having lived that life even for a very short time, is that we simply didn’t understand the material meaning of that technology or of our rejection of it. Milking cows by hand, digging vegetable gardens, chopping the wood you need to keep warm in winter, shearing sheep, all this is very hard and very exhausting physical work and the rewards for that work are meagre. I wonder if we as humans haven’t spent our entire history desperately trying to get away from having to do that sort of labour in order to get our daily bread? I think there was a writer in the 1970s ( it might have been Arthur C. Clarke, who wrote 2001: A Space Odyssey) who said that the everyday things we take for granted, from turning on a tap to making a phone call to flying in a plane, for our ancestors would be indistinguishable from magic. And that was before the revolutions of the last fifty years! But these are complex and contested ideas.

My experience as a child has led me to appreciate both sides of this story in a very visceral way. I can testify that when you have spent half an hour trying to squeeze a pint of milk out of a reluctant and bad-tempered cow and then she sticks her hoof in the milk bucket, having first stuck it in a pile of manure, the romance of the idea of self-sufficiency is far from your mind! But that is only one aspect of the experience. I treasure the memory of the beauty of the place, the warmth of the companionship and the incredible pleasures of having created something new and useful and lovely out of the earth.

The jumper is a beautiful example of how an object can carry emotions and historical information. I’m not sure what might happen to the jumper, and the story. Does it really have historical significance? Might a museum want it? Or will some great-grandchild of mine want to preserve it and understand it? I hope they will.